Shield of faith or tool of discrimination?

Indiana Religious Freedom Law causes controversy

Have you seen the hashtag #BoycottIndiana on Twitter lately and wondered what Indiana did wrong? The hashtag has even been used by several notable celebrities and politicians. According to Topsy, over 200,000 people have used the hashtag so far, and the reason for this is Indiana’s recently signed religious freedom law, Senate Enrolled Act 101. The law has been met with intense controversy; some believe that it allows businesses to discriminate against customers based on sexual orientation and gender identity, while others see the law as a necessary protection of religious rights that simply mimics legislation already in place at the federal level. As the debate over this divisive law rages on, there is no denying that the clash between religious rights and non-discrimination will be a hot political topic for some time.

Indiana’s version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) was signed by Indiana Gov. Mike Pence on March 26. It decrees that state and local governments must refrain from “substantially burdening” a person’s religious freedom unless they can prove that they have a compelling reason to do so and can do it in the least restrictive way. The law has been met with intense criticism. In an interview with The Indianapolis Star, Senate Minority Leader Scott Pelath said that the law would undermine the state’s ability to protect against discrimination and that it would demote LGBT people to second-class citizens.

“It basically says to a group of people, ‘you’re second rate, you don’t matter,”’ said Pelath, “‘and if you walk into my store, I don’t have to serve you.’”

Gov. Pence, however, does not see the new law as discriminatory. Before signing the law, he issued a statement describing the law’s purpose.

“The legislation, SB 101, is about respecting and reassuring Hoosiers that their religious freedoms are intact,” Pence said. “I strongly support the legislation and applaud the members of the General Assembly for their work on this important issue.”

Once the law was signed, Pence was met with national criticism from business leaders, civil rights groups, and even celebrities, prompting him to sign an amendment. The compromise legislation, according to Senate President Pro Tem David Long in an interview with The Indianapolis Star, makes clear that the original law was not meant to support discrimination. The revision “unequivocally [states] that Indiana’s [religious freedom] law does not and will not be able to discriminate against anyone, anywhere at any time.”

The amendment is also the first time that Indiana legislation has included the language “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” in a non-discriminatory context. Ms. Lisa Robinet, a Mercy government and history teacher, believes that the law’s intent was to protect religious freedom, not infringe on people’s rights. She did, however, say that the amendment was extremely necessary for the law to be interpreted correctly.

“I think that clarification needed to be made on what owners of businesses could and could not do,” said Robinet, “because the law was written in such a way that people assumed that if you had a problem with a gay person coming in to your store, you could refuse them service. That’s not what the law was intended for.”

Some companies and organizations do not see the amendment as enough. According to The Indianapolis Star, Angie’s List was the first major company to reject the compromise.

“Our position is that this ‘fix’ is insufficient,” said Bill Oesterle, CEO of Angie’s List. “There was no repeal of RFRA and no end to discrimination of homosexuals in Indiana.”

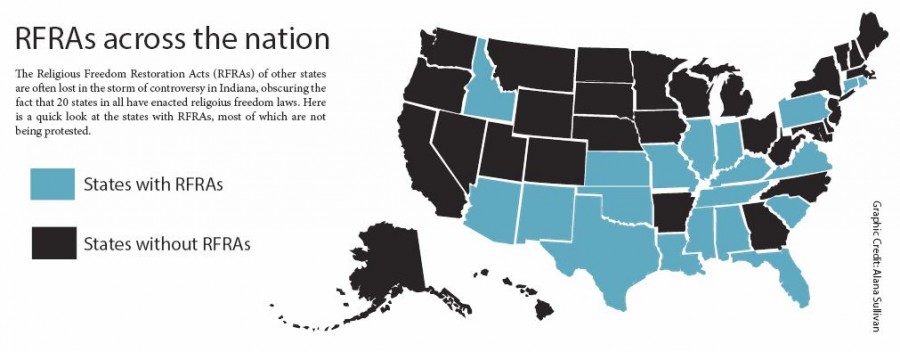

With the debate over whether the amendment is adequate still raging in Indiana, many have overlooked the fact that 19 other states have enacted similar RFRAs. For example, Alabama’s law is narrower in scope than the Indiana bill, but addresses similar issues. Alabama lawmakers are currently considering introducing a new RFRA that is comparable to Indiana’s. Gov. Pence referenced the Illinois RFRA in his defense of the Indiana bill, saying that President Barack Obama supported the law when it was passed in 1998. The Illinois law, however, is supplemented by a statewide statute protecting LGBT people from discrimination. The Florida RFRA is only slightly less far-reaching than the Indiana law, yet it was backed by both the American Civil Liberties Union and the Christian Coalition. Why did these states escape unscathed while Indiana was caught in a storm of controversy? Ms. Robinet says that there is no definitive answer to this question, but she has a few theories.

“I don’t know if it’s because the other states’ laws are more similar to the federal law,” Robinet said, “or if it’s because the college basketball finals were being played in Indiana during that week. It’s very curious.”

The federal law that Robinet referenced is the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. The difference between this law and laws passed at the state level is that the federal RFRA only protects citizens from the federal government, not state governments. State RFRAs are designed to protect citizens’ rights from infringement by state governments.

Whatever the reason for the turmoil around Indiana’s religious freedom law, Ms. Robinet still believes that the important thing is to make sure the law leaves all citizens’ personal liberties intact.

“If you own a business, being religiously against something does not mean that you can exclude people with different values or morals than you from service,” said Ms. Robinet. “I may not agree with something, but I’m not going to infringe on your rights just because I don’t understand you.”